Hidden treasure: Why Oregon’s native bees need you this fall

October 02, 2025

As fall starts to settle in the Pacific Northwest, blooms turn to seeds, deciduous trees blush with warm shades and crisp mornings bring a sense of change. In the same way that the cooler weather might make you want to curl up inside with a good book and a hot cup of tea, the fall shifts native bee behavior, with many settling into hibernation mode, though, their winter homes look quite different from ours.

Oregon’s bees use this time of year to nestle in for winter. During the colder months, they’re often hidden in plain sight, beneath leaf litter, inside hollow stems or tucked into bare patches of soil. Though unseen, many of our vital pollinators persist—dormant within their winter refuge—until seasonal changes stir them to join the buzz of spring. You can help protect their secret winter homes whether you’re a gardener, land manager, or just someone who loves Oregon’s wild beauty.

Oregon is buzzing with bee diversity. You may be surprised to discover that the state is home to more than 750 species of bees and that number keeps growing! While we often picture social bee species such as honeybees that live together in hives, most of Oregon’s native bees lead a much more solitary lifestyle. The majority don’t form colonies or defend a hive. Due to their passive nature, they can easily be overlooked, however, healthy native bee populations in Oregon are imperative to support the rich habitats of our state.

About 70% of Oregon’s native bees are ground nesters, including bumble bees.

Some ground-dwelling species such as bumble bees mate in late summer or fall and only the mated females live on through the winter to carry on the lineage. As these new queens emerge, they seek shelter for the long winter ahead. Like springtime behaviors associated with ground nesting, bumble bee queens can be observed in the fall buzzing low over leaf litter, checking out old burrows, and exploring bare soil. Amazingly, once bedded down, fertilized bumble bee queens can go dormant by flooding their systems with a naturally produced anti-freeze (glycol), allowing them to persist through the peak cold months in just a few inches of leaf litter. So, when folks mention that we should consider “leaving the leaves” all winter, it’s to the bees’ benefit!

While many of our native bees overwinter in the ground, others prefer a home with a view. Cavity-nesting bees will tuck themselves into tree knots and old beetle burrows or dig out the soft centers of twigs to create their winter refuges. Take the small carpenter bee (genus Ceratina) for example. These bees create perfectly protected overwintering sites within stem cavities, complete with a pollen ball for their larvae to feed on. Interestingly, some cavity-dwelling bees also practice site fidelity and are known to return to the same twig where they were born to lay their eggs.

You may have heard about the decline of honeybees, but are we also concerned about our native bees? Yes. Unfortunately, there are many compounding threats. If you would like a deep dive into what researchers and managers are concerned about, we encourage you to look through the Oregon Bee Project’s strategic plan. Section two of the plan specifically addresses challenges our native bees face.

We hope after reading this you’re inspired to support bee habitats this fall. Here are a few key takeaways to get you started:

- Use native seed mixes.

Sowing native plant seeds in the fall can be an economical approach to developing habitat over time. If you go for this approach, be sure to consider impacts to overwintering bees when prepping the planting site. We recommend the “one third” approach for intensive management strategies such as herbicide applications and the use of fire. In other words, only treating up to a third of the available bee habitat in any given year. This will ensure that native species already present at the site can recolonize. - Skip the yard clean-up (even just a little).

Leaving some leaf litter and bare patches of soil in your yard gives ground nesters and overwintering queens a safe place to ride out the cold months. - Leave the stems.

When pruning plants, leave 8–10 inches of stem. These leftovers harden over time and make great homes for cavity-nesting bees. - Protect overwintering bee habitat.

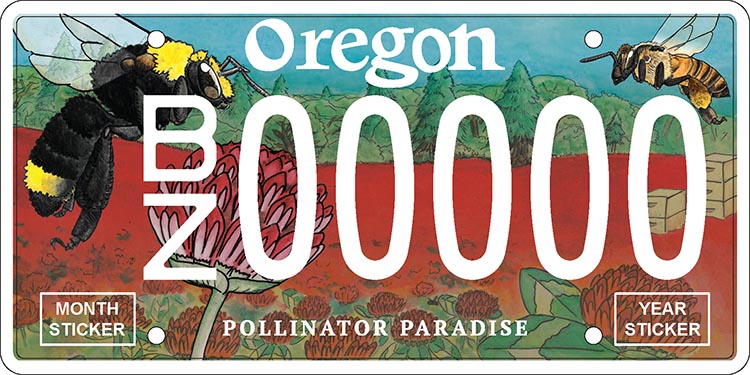

A protected area filled with a mix of native plants that bloom at different times of the year, including winter, can be a huge help to pollinators. Winter blooms offer early food for bees that might emerge ahead of schedule due to warmer temperatures. - And lastly, get involved! There are so many ways, big and small, available to you. One place you can start is by checking out the Oregon Forest Resources Institute’s Wildlife in Managed Forests: Native Bees publication to learn about bee-friendly forest stewardship. The Oregon DMV also now has a pollinator license plate, and you can even become an expert on bees in Oregon through the Oregon State University Extension Service’s Master Melittologist Program.

It can’t be overstated that Oregon’s pollinators are as varied as the landscapes they inhabit. With hundreds of species and counting, there is so much yet to be discovered about them. There are also plenty of small actions to take that have lasting benefits. So, when the leaves start to drop this fall, let’s help bees settle in for winter and make sure they’re ready to greet spring with a buzz!

Eliana Pool

Wildlife Biologist, Cafferata Consulting

Heather Thomas

Wildlife Technician, Cafferata Consulting

Resources:

Oregon State University: Bees in the woods video series

Native bee interactions with plants in Oregon

Tool: Bee interactions with plants in Oregon

Seed Germination and Propagation Reference Guide

Bee Identification:

Pocket guide for identifying the rare Western bumble bee

Bees of the Pacific Northwest: key to bumble bee species for females (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus)

Bees of the Pacific Northwest: key to bumble bee species for males (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus)

Key to simplified subgenera of the genus Bombus for female bumble bees (Williams, 2008)

Key to simplified subgenera of the genus Bombus for male bumble bees (Williams, 2008)