OregonForests.org examines complex forest issues and provides a broad overview on a variety of topics. Of course, sometimes people just have questions about the basics.

Below is a list of frequently asked questions. These questions have been answered by working foresters.

Don’t see your forest-related question answered here? ASK ONE OF OUR FORESTERS.

Frequently asked questions:

What is Oregon’s law regarding replanting?

The Oregon Forest Practices Act requires forest landowners to replant after harvest. A landowner must establish the next generation of trees soon after a harvest. The trees must be planted within two years, and they must be evenly distributed and free to grow (free from competing vegetation) within six years. This is a higher standard than simply replanting seedlings.

You advertising says "40 million trees planted every year." Can you explain that math to me?

Recently, you may have had the pleasure of seeing one or more of OFRI’s educational ads. We’ve been focusing on reforestation after timber harvest, and frequently tout the fact that every year Oregon forest landowners plant 40 million seedlings. Many people believe this fact at face value, but some wonder "How is it possible to plant 40 million trees every year?"

40 million seedlings may seem like a lot, but a good tree planter plants 1,000 to 1,200 seedlings per day. Planting season is generally from Dec. 1 to March 31, which is about 88 work days. If each tree planter plants 1,000 trees per day for 88 days, that’s 88,000 trees per tree planter per year. It would thus take 455 tree planters about 88 days to plant 40 million trees.

That seems pretty doable – but it isn’t easy work. Most of the work of tree planting takes place in cold and rainy weather, on steep and rugged terrain. My hat goes off to the tree planters who put each seedling in the ground by hand.

Why are we exporting logs instead of processing them into lumber here?

Periodically, exporting whole logs becomes a hot topic in Oregon. In recent years, companies have exported, mainly to China, an increasing number of logs from private lands. It is illegal to export logs from state or federal lands.

The current cycle of log exports coincides with a stagnant domestic economy, where demand for lumber is at an all-time low. In the meantime, China’s economy has been growing. There, buyers use timber mainly for building concrete forms. They prefer to saw the logs to their own specifications using inexpensive Chinese labor.

The export cycle ebbs and flows, and there have been long periods when few logs were exported. In the future, Oregon manufacturers may have opportunities to process timber into higher-value products such as doors, windows and engineered structural components for export. However, markets can change rapidly. It would be a hardship for small and large private landowners if domestic markets were depressed and they were barred from selling some logs in export markets where prices are attractive. The export market employs many loggers, truckers, dock workers and foresters.

Given the growth of high-tech, is there a future for the forest products industry in our state?

Oregon’s high-tech sector some time ago passed the state’s forest sector in terms of wealth created by selling products to domestic and international markets. However, despite a down economy and a shrinking timber harvest from public lands, the forest products sector continues to be the largest driver of Oregon’s rural economy. A weakened forest sector in rural Oregon acts as a drag on urban Oregon because of the many linkages between Oregon’s larger cities and smaller towns.

Wouldn’t it be better to build our rural economies around recreation and tourism instead of forestry and logging?

The forest products sector is needed to help maintain healthy forests. Without foresters, scientists, loggers, truckers and others, as well as the mills to process timber, we would not have the infrastructure to provide the forest products we use every day or to sustain forest health and fire resiliency.

Recreation, tourism and forest products manufacturing are compatible uses of our forests. However, recreation and tourism tend to be seasonal and produce fewer family-wage jobs. Forest management, milling and manufacturing produce steadier work and the largest portion of Oregon’s high-quality rural jobs. Direct forest sector jobs pay, on average, more than $44,000 per year, somewhat higher than the average Oregon wage, and most come with benefits. Those jobs also drive important secondary jobs in rural communities. Often, the forest sector jobs underpin economic health in Oregon’s small cities and towns, which in turn helps Oregon’s urban economy.

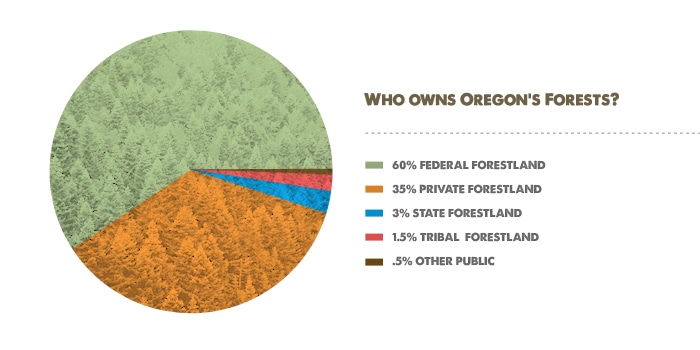

Who owns Oregon’s forests?

Oregon’s forestland landscape is nearly 30.5 million acres, nearly half of the state’s landmass. About 60% of these forests are managed by the federal government in public ownership. About 19% are owned by large private landowners and managed primarily for timber production. Another 15% are smaller tracts, less than 5,000 acres, owned mostly by families and individuals. Families have diverse management objectives, but many depend on these lands for intermittent income. The state, counties and towns own another 4%. Two percent is under tribal ownership.

What’s the problem with federal forests in Oregon, and what can be done about it?

There is no single problem with federally managed forestlands, although there is general agreement that passively managed federal forestlands east of the Cascades and in the interior southwest have a set of readily identifiable problems that could be addressed using active forest management.

These so-called dry-side forests have grown denser and therefore present ever-greater fire risk during hot, dry periods. Due to effective fire suppression and other past management practices, many of these forests are at risk for insects, disease and uncharacteristically severe wildfire. Historically, lightning-sparked fires typically would have removed competing understory trees and brush as often as every five years. Left unchecked, the biomass competes with the larger, dominant tree species for scarce water and nutrients.

Today, there are millions of acres of overstocked, stressed trees in dry-side forests that could be thinned by removing surplus biomass and saw logs where appropriate. Thereafter, prescribed fire where safe and appropriate could maintain these forests in a more natural, fire-resilient state and with a more natural appearance.

What is the relationship between mountain pine beetle damage to our east-side forests and the risk of catastrophic fire?

Mountain pine beetles occur naturally in dry-side forests. They have become infamous for their attacks on lodgepole pine stands throughout western North America. The natural cycle for lodgepole pine is to grow in dense stands until trees are about 100 years old, when they are killed by mountain pine beetles and then burn up in large fires that start new stands. Currently, because of past fire suppression, mountain pine beetles are killing a large supply of overly mature lodgepole. The beetles are also causing more death among ponderosa pine than has been usual. As the trees are attacked and die, they provide the fuel for hotter, more destructive fires.

While there are some downsides to excluding fire from some forest stands, Oregon prides itself on a long and successful fire protection program. Landowners work cooperatively with government agencies to keep fires small to protect watershed health and air quality, as well as homes and human life.

Should we encourage bio-energy facilities in Oregon?

For more than 100 years, woody residuals from harvesting and milling trees into forest products have been used to produce heat and generate electricity. The biomass plants conform to stringent boiler standards to ensure that their emissions meet current air quality standards. Demand for energy will continue to increase. Innovative utilization of Oregon’s abundant forests, similar to steps countries in Scandinavia and Europe have taken, may provide opportunities to meet some of this demand.

Debate about removing biomass as part of treatments to restore forest health and fire resiliency has prompted questions as to whether forest biomass is carbon neutral. Most scientists regard forest biomass as carbon-neutral because it is part of a continuous cycle of CO2 absorption and release. The release of CO2 from fossil fuels, by contrast, cannot be absorbed on anything less than a geologic timescale.

Dead, decaying trees are themselves sources of atmospheric carbon. And so is forest fire that destroys forests and releases large amounts of carbon in short bursts, and then even more as killed trees decay or burn again.

Removing biomass, including small to medium-size trees, to restore sickly forests and using it to produce renewable energy can displace some fossil fuel use and offset carbon emissions from those sources.

Shouldn’t we stop cutting timber so we can store carbon in forests as a means to offset greenhouse gases?

As with many forest issues, there are at least two sides to this issue.

Oregon’s forests are dense and packed with carbon-rich wood. Over the past 100 years, we have attacked forest fire with such vigor that forests have expanded and the overall density of these stands has increased, sometimes manyfold. Leading up to the 20th century, some of the most accessible forests in Oregon were severely burned over or visibly recovering from past fire. The historic record shows that there were large patches of very dense old-growth forest that stored lots of carbon, but there were also many forests recovering from stand-replacing fire.

Managing forests primarily to store carbon might benefit some wildlife species but would devastate others. Managing for ever-denser stands of wood also promotes conditions that could lead to uncharacteristically severe fire during periods of hot, dry weather. Managing forests for health and fire resiliency as well as for the forest products we use every day is a sensible approach. About half of the wood in various forest products is carbon, and it will be stored for the life of the product. Above all, keeping forests as forests allows for continued clean water, fish and wildlife habitat, and a level of stable-to-increasing carbon storage.

Why don’t we classify forest roads as point sources of pollution just like factories?

Since passage of the Clean Water Act in 1973, forest roads have been regulated as non-point sources of pollution. Changes over time to forest practices acts and best management practices have proved effective in keeping up with emerging science on how best to control runoff from logging roads. Changing roads’ classifications from non-point to point sources would be costly for states to administer and would likely generate no more environmental benefit than the current system of laws, regulations and best management practices. Further, a point-source system would leave private forestland owners open to citizen lawsuits, putting a further damper on private forest ownership and timber production.

Regulating runoff from forest roads as point-source pollution overturns decades of laws and rulemaking that have already brought significant and continuous improvements to forest streams, fish and wildlife habitat, and water resources.

Systematic regulation of runoff from forest roads under the Oregon Forest Practices Act over the past 40 years has moved thousands of miles of roads away from streams and closed thousands more. Today, timber is harvested using cables that hoist it above the ground, and moved to hilltops where improved road systems move it out. The impact from roads has been lessened in other significant ways, too.

Some roads cannot be moved, so other regulations have been developed, including:

- Engineered systems are required to ensure that water from road surfaces drains away from streams.

- It is never acceptable to drain water from roads directly into streams.

- Road surfaces must be engineered and hardened to lessen impacts from trucking.

- Roads typically are closed to traffic when not in use and may be decommissioned and replanted if they are no longer needed.

- Roads are closed during extreme wet weather to reduce siltation.

- Landowners have improved thousands of stream crossings by installing appropriate-sized culverts or constructing bridges.

Oregon’s Forest Practices Act recognizes that making real and permanent improvements to forest roads is a continuing process that demands tremendous investment over time. Therefore, the law requires that these improvements be made as roads are needed in areas where future timber harvest is planned.

Why do landowners clearcut?

A clearcut is an area of forestland where most standing trees are logged in a single operation and few trees remain after harvest. Forested buffers are left around streams and lakes, and the area is then replanted within two years of harvest. Clearcutting is a controversial method of tree harvesting because of its visual effect on the landscape.

In western Oregon, clearcutting can be the most appropriate harvesting method for certain tree species. For example, clearcutting is often used in Douglas-fir forests because new Douglas-fir seedlings need direct sunlight to grow quickly. In eastern Oregon, the most common tree species are more shade-tolerant, and therefore, clearcutting is not a preferred harvest method.

Douglas-fir is ecologically adapted to disturbances such as intense fire and windstorms. In Oregon’s Douglas-fir growing region, nearly 80% of the landscape would eventually self-seed as nearly pure stands of Douglas-fir with some western redcedar, red alder and a small variety of other trees. Douglas-fir seedlings do not grow well in the shade. Clearcutting is used to mimic the ecology of stand-replacement fire or other disturbance so that new stands can grow. Because a clearcut receives more sunlight, not only do Douglas-fir seedlings thrive but so do sun-loving shrubs, herbs and grasses that provide forage for grazing animals such as deer and elk.

Clearcutting Cons:

- Appearance. Until the newly planted trees “green up” a hillside, a clearcut is not considered visually appealing.

- Habitat disturbance. Clearcutting alters the habitat where the trees once stood, and the forest’s inhabitants are displaced into different areas.

- Increased stream flow (both a pro and a con). Clearcuts allow more water to enter a stream system through subsurface flows because the water is not being taken up and released by trees, a process called evapotranspiration. Increased stream flow can lead to increased riparian erosion during high-water occurrences. On the other hand, increased flow during low-flow periods helps cool streams and provides better habitat for fish and other aquatic life.

Clearcutting Pros:

- Full-sun conditions. Wide-open spaces allow the most sun for species that require full-sun conditions to thrive. These conditions also create quality wildlife habitat for species such as deer and elk and some songbirds that prefer shrubby young forests.

- Economy of harvest. Clearcutting represents the most efficient and economical method of harvesting a large group of trees.

- Fewer disturbances to the forest floor. By entering a forest stand once, instead of multiple times for repeated harvests, the landowner minimizes disturbance to forest soils.

Clearcutting Regulations Under Oregon Law:

- Clearcuts must be replanted within two years.

- Clearcuts may not exceed 120 acres in size.

- Forested buffers must be left along streams, lakes and wetlands.

- Adjacent units may not be clearcut until seedlings are well established and free to grow.

- Landowners must provide forested buffers when the unit is next to a scenic highway.

- Landowners must leave two standing live or dead trees and two down logs per acre as wildlife habitat.

What is the required logging buffer zone for scenic byways? Take Highway 242, for example...

Thanks for your question. This is an interesting one. There are two scenic highway programs in Oregon.

- The Oregon Scenic Byway Program is managed by the Oregon Department of Transportation in association with the National Highway Administration. This is mainly to identify highways that tourists would like to drive. The McKenzie Pass – Santiam Pass Scenic Byway is one of these and has been since 1997. There is no formal regulation of private land within this corridor as far as I can tell. The management plan developed by the Forest Service only governs land in the Willamette and Deschutes National Forests, which is most of the land along this route. As far as I can tell, there is no special regulation of private forestland along the route other than the Oregon Forest Practices Rules.

- Designated Scenic Highways are a designation in the Oregon Forest Practices Rules that specifies the logging buffer on designated highways. I have attached a PDF of a couple pages from our Oregon’s Forest Protection Laws: An Illustrated Manual that describes this program. As you can see from the list in the first paragraph, Oregon Highway 126 is designated as a scenic highway, but Oregon Highway 242 is not. I believe that this is because most of the land along Highway 242 is National Forest land and the Oregon Forest Practices Rules only apply to private and state land.

So, I believe that there are no required logging buffers along Highway 242, except for areas that are within the Riparian Management Area of a river or stream. These buffers are up to 100 feet on both sides of a large fish-bearing river like the McKenzie, down to only 50 feet along a small fish bearing stream.

I would also recommend that you contact your local Stewardship Forester with the Oregon Department of Forestry. These are the folks who enforce and help interpret the Oregon Forest Practices Rules and other regulations that apply to private forestland in Oregon. The McKenzie River area is included in the East Lane District of ODF. The office is at 3150 Main Street in Springfield. The phone number is 541-726-3588.

If you would like a copy of the Oregon’s Forest Protection Laws: An Illustrated Manual, let me know and I can send you one. You can also download a PDF file of the entire manual from the OFRI publications page at: https://oregonforests.org/publication-library/oregons-forest-protection-laws-illustrated-manual-2025. This publication and all other OFRI publications are available at no charge.

Where can I purchase forestland? I'd like to get involved and start ownership of a family forest.

This is a great question. I know of three basic ways to find forestland available for purchase.

- Use a local or regional realtor. Most local areas in Oregon with much forestland have a realtor or two who specializes in forestland and rural acreages. You can usually find who by going to the website of your local Multiple Listing Service and see who lists rural acreages. There is also a regional realtor called Realty Marketing / Northwest (www.rmnw-auctions.com) that specializes in forested acreages. Many of these are lands that are owned by timber companies that want to sell them for various reasons.

- Use a local consulting forester. Most consulting foresters do a lot of timber cruising, and many do forestland appraisal. Because of this they often know which properties in their area are coming up for sale, but may not yet be listed with a realtor. Some consulting foresters also are real estate brokers. A list of consulting foresters is available from the Association of Consulting Foresters at: www.acf-foresters.org/ The Society of American Foresters has a Certified Forester Program. Many of the Certified Foresters are consulting foresters. The list of Certified Foresters is available at: http://www.safnet.org/certifiedforester/index.cfm.

- Use the local forest landowners network. Most forest landowners are very knowledgeable about who in their area is selling or buying land. A good group to network with is the Oregon Small Woodlands Association. With 20 county-based chapters and over 1,500 members, there are great opportunities for networking. A list of OSWA chapters and officers is available at: www.oswa.org.

Why are there so many dead trees on Mckenzie Pass?

Both of these situations are part of the natural cycle. When stands become overcrowded some trees die, while others are attacked by defoliating insects and others are attacked by bark beetles. The natural cycle of lodgepole pine (one of the most common trees in the high Cascades) is to seed in after a forest fire, grow more slowly in very dense stands, grow even slower as they reach 100 years old, be killed by bark beetles, eventually be burnt up by a wildfire, and then start the cycle over with a new stand of seedlings.

In many areas, projects are planned to salvage dead trees and thin out live trees to improve their health. However, some areas along the McKenzie Pass Highway (242) are within the Three Sisters Wilderness to the south and the Mount Washington Wilderness to the north. In these designated wilderness areas, no logging is allowed. This includes thinning and salvage of dead trees. In these areas the foresters' only option is to prepare for the inevitable wildfire. This is a real threat this time of year, when high temperatures, low humidity and dry east winds converge to take advantage of any spark or stray lightning bolt.

To add local-expert clarification to your question, I am copying Kevin Moran. Kevin is Timber Stand Improvement forester on the McKenzie River Ranger District of the Willamette National Forest. Kevin is intimately familiar with the dead tree situation on McKenzie Pass and has been leading projects on the district to salvage dead trees and thin live ones to improve forest health and reduce the risk of wildfire.

I hope my answer is helpful and I hope that Kevin is able to provide additional clarifying information.

Thanks for asking a forester!

What is typical percentage by mass of water in a tree?

The percentage of water in a tree can vary quite a bit depending on species of tree, part of the tree in question, season of the year, time of day, health of the tree and whether it is living or dead.

Percentage of water is generally expressed as Moisture Content on a dry-weight basis.

Moisture Content, % =

weight of water in sample X 100

_______________________________________

oven dry weight of sample

...OR...

Moisture Content, % =

weight of sample with moisture – oven dry weight of sample X 100

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

oven dry weight of sample

Moisture Content of leaves, needles and twigs varies from over 150% in the spring and early summer when water is plentiful to <25% during the dry part of the summer. Moisture in needle and leaves has been used as a measure of the drought-induced stress that plants are under this time of year. Leaves and needles go from a high moisture content in the early morning to a lower content later in the day. This is called diurnal variation and is driven by solar radiation and relative humidity of the atmosphere. Plants that are under intense drought stress do not recover the moisture content of their leaves overnight, so early morning or pre-dawn moisture contents are very low.

Moisture Content of wood varies by species of tree, health of tree and whether sapwood or heartwood. Green wood of live trees in the forest is usually thought of being about 100% moisture content. Thus a chunk of fresh cut wood would have ½ of its green weight made up of water and ½ made up of wood.

However, a study of lodgepole pine in British Columbia by R.W. Reid, published in Forestry Chronicle, showed a steep moisture gradient from about 160% for the outer sapwood nearest the bark to 30% in the heartwood in the center of the tree. This makes perfect sense when you understand that the sapwood’s function is to conduct water from the roots to the leaves or needles, while the heartwood’s function is to provide stability.

The same study showed the moisture content of outer sapwood of healthy lodgepole pines varied from 85-165% and that attack by mountain pine beetle causes the sapwood moisture content to drop to as low as 16% because of the blockage of vessels in the sapwood by blue-stain fungi.

Standing dead trees can have Moisture Content in their wood as low as 20-30%. This is really dry, especially when you consider that air-dried lumber ends up at about 20% Moisture Content, while kiln-dried lumber ends up with about 10% Moisture Content.

Finally, there are moisture meters that can instantly estimate the amount of moisture in a given piece of wood. These function by sticking two needle-like probes in a piece of wood and measuring the electrical conductance between them. Higher Moisture Content has higher conductance because water conducts electricity much better than wood does. These meters can be calibrated to give fairly accurate Moisture Contents.

So Jeff, the answer to your question, like many forestry questions, is “It depends and it varies.” However, it is commonly said that green wood has around 100% Moisture Content, and this is probably a fair generalization, considering all of the variables.

Thanks for asking a forester.

Is there somewhere to get help replanting after a clearcut?

There is help available to replant a clearcut in terms of technical assistance. The Oregon Department of Forestry has Stewardship Foresters in every county in Oregon, whose twofold job is to enforce the Forest Practices Rules and to assist private landowners.

The attached link to the Assistance Map in KnowYourForest.org can be used to find your local Stewardship Forester. Just select your county and find your Stewardship Foresters.

http://knowyourforest.org/assistance-map

The map also lists Extension Foresters with Oregon State University, who cover most forested counties in Oregon. Extension Foresters primarily lead workshops and tours, but in many cases can provide one-on-one assistance.

Unfortunately, financial assistance to replant a clearcut is not available in Oregon. Since the Forest Practices Rules require planting after clearcutting, the limited financial assistance is targeted to planting areas being converted back to forestland or rehabilitating after wildfires.

I watched an online video called "Clean Water or Clear Cuts" about forestry in Oregon. Why don't we replant the trees after a clearcut?

Thanks for your question.

In fact, planting trees after harvest is the LAW in Oregon. The Oregon Forest Practices Act requires that a minimum of 200 trees per acre be planted within two years of harvest and that they be "free to grow" by six years after harvest. The Oregon Department of Forestry enforces this law through its Stewardship Foresters. The program is currently undergoing a compliance audit. The last audit, done a few years ago, showed 90-95% compliance among private landowners.

There's lots of information on clearcutting and forest protections laws on our site. Have a look around, and thanks for asking a forester.

Is it legal to export logs from public forestlands? How do they track those logs to make sure?

First of all, I don’t know if export is illegal from all public lands. It is explicitly forbidden from federal lands by federal law and from state lands by state law. Prohibition from county or city lands would be based on prohibition by those levels of government.

With state and federal logs, tracking is done by branding and painting of logs and communication from the purchaser telling the timber sale contracting officer exactly where logs from the sale are going, what brand is being used and what paint color is being used. Loggers typically use their own brands, but the government assigns the paint color. Typically all federal logs are painted with yellow-paint on at least one end of each log. Log exporters are on the lookout for yellow paint logs.

I hope this helps. Thanks for asking a forester.

Can I cut down a tree from the wild forest for my own Christmas tree?

Thank you for your question. The answer is yes, you can cut down a Christmas tree from the wild forest, if you have a permit. Most private land is closed to Christmas tree cutting, but much public land is open.

Nearly all National Forests in Oregon sell Christmas tree permits for $5 at the local ranger stations. They will also give you maps to tell you where the best areas are.

Information on National Forests can be found at: http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r6/home/?cid=fsbdev2_026675. When you get to this page, scroll down for a map of Oregon and Washington National Forests and links to each forest's homepage. Some of these, such as the Deschutes and Willamette, have specific links on Christmas tree permits and areas. All have contact information for each Ranger District where you can find out if permits are available, if certain areas are open or off-limits, and if there are seasonal road closures due to snow.

The Forest Service has also put together a nice video on getting a Christmas tree from the forest. It can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgfpMhJOtK0&feature=player_embedded

The real key is to be safe. The best wild Christmas trees are the noble and Pacific silver firs. These grow at higher elevations where weather and roads can be troublesome in December.

Happy hunting, and thanks for asking a forester.

In general, how late into the winter season can replanting be delayed without risking loss of crop? As a reference, please consider replanting this year, a central Lane County location, and Douglas-fir in your response.

In general, tree planting season in western Oregon is January-March. However, planting in early April can be successful, if there is cool, wet weather, good soil moisture and the seedlings have been kept refrigerated since lifting.

The planting limits of the planting season are determined by three physiological events in the tree's annual growth cycle:

- Dormancy – bare root seedlings should not be lifted from the nursery until fully dormant. This depends on accumulation of chilling days, which doesn’t usually happen until late December.

- Root growth – conifers have two big seasons of root growth: October and March. Many foresters like to have their planting done before March 1, to take advantage of the March root growth. Planting later keeps the seedlings dormant, and root growth doesn’t start until planting. Delaying this until early April is not a problem unless there is a really dry spring.

- Bud break – Douglas-fir normally has bud break in early to mid-April, depending on the weather. Bud break is often later in colder springs. Delaying planting will delay bud break and can cause planting shock.

All this being said, many foresters and woodland owners have pushed the limits and planted as late as June 1, often with success. However, planting after early April can significantly reduce survival for the reasons stated above.

The other thing to take into consideration is soil moisture when planting. It is generally recommended that the soil be moist at least a foot down before planting. In dry falls, it may be better to wait until after the winter rains set in to begin planting. I would definitely dig a few test planting holes and see what the soil moisture is like before picking up the seedlings from the nursery.

Thanks for asking a forester.

Was Oregon all forest at one time?

Great question, on whether "Oregon was all forest at one time." It depends on what you mean by "one time." In geologic times with dinosaurs and what-not, Oregon may have been all forest.

However, in recorded history, which goes back to the 1600s here, Oregon has always been about one-half forest. The west-side valleys such as the Willamette, Umpqua and Rogue were historically prairie and savannah. Central and eastern Oregon have large areas of rangeland and high desert that don't have enough rainfall to support forest. It takes a minimum of 15-20 inches of precipitation per year to support forest cover, and much of the east-side gets less than that.

Estimates made by U.S. Forest Service researchers are that in 2007 Oregon had about 99% of the forestland it had in the 1600s. Some forest has been lost due to agriculture and cities, primarily in western Oregon. Some forest has been gained by encroachment of forest onto previous grasslands and savannah, primarily in central and eastern Oregon.

Oregon has very strong and effective land-use planning laws to protect forestland and keep it from being converted to other uses.

I hope this answers your question. Thanks for asking a forester.

Who does custom debarking for export logs?

One place that I know of that does custom debarking is Teevin Brothers Log Yard in Rainier, OR (www.teevinbros.com).

I was on a tour there a couple years ago and saw them debarking logs for customers, who then hauled them across the bridge for export in Longview, WA, at the Weyerhaeuser yard.

The debarking is necessary to prevent importing pests in the receiving country. The other option is fumigation, which is more expensive and less available.

I hope this helps. Thanks for asking a forester.

What is the purpose of all the tree cutting along the highway from Klamath Falls to Bend?

The tree cutting on Highway 97 between Bend and Klamath Falls is being done in the Oregon Department of Transportation right of way. It is for two reasons. First, to daylight or open the highway to more sunlight. This will allow the road to dry faster and reduce the amount of ice in the winter. Second, the cutting is to create a fire break in a very fire-prone forest. Past fires in Central Oregon have burned right across roads and highways if there is forest fuel along the road.

You will also notice some moderate thinning in the adjacent National Forest and private land along Highway 97. This is to reduce the fuel loading, remove ladder fuels and reduce crown density. All of this helps make the forest more fire-resilient. Fire will always be part of these forests, but through active management, we can help with the fire management and reduce the risk of having a stand-replacement fire that kills most of the trees.

Thanks for asking a forester

Is the property owner responsible for weed control after clearcutting their land?

Weed control is not addressed in the Oregon Forest Practices Act. However, effective reforestation is. The landowner is required to begin the reforestation process within 12 months of harvest, have trees planted within 2 years of harvest and have 200 trees per acres "established" as "free to grow" within 6 years of harvest. That may require weed control or it may not, depending on the site. If the reforestation effort fails due to excessive competition from uncontrolled weeds, the landowner may be fined.

I know that some counties have noxious weed ordinances, and landowners with noxious weeds on their properties are encouraged to control them. However, I know of no statewide requirement to control noxious weeds.

I hope this answer helps, and thanks for asking a forester.

I've heard that private timberland owners have to get the permission of those living within 5 miles to log one's own land. True or crazy talk?

I know of no such rule in Oregon requiring landowners to get permission from any neighbors before logging. Logging on private land in all of Oregon is governed exclusively by the Oregon Forest Practices Act. Unlike in some states, Oregon counties are not allowed to have forestry rules. The exception to this is that within urban growth boundaries, municipalities are allowed to have tree ordinances that could govern forestry within the UGB.

A notification to operate must be filed with the Oregon Department of Forestry at least 14 days before a logging operation is to begin. In certain cases, such as operating near a fish stream, a landslide-prone landform or a protected species, a written plan must be filed. Citizens, including neighbors, can get access to notifications, and landowners are encouraged to notify their neighbors of plans to log. However, no permission from any neighbors, or public is required.

I follow the Oregon Legislature pretty closely and have not even heard of such a law being proposed.

I hope this answer helps you. Thanks for asking a forester.

I've noticed that most places that have been logged always have a single tree that wasn't ever touched. Why is that? Is it structural, mandatory, wrong tree species or something else?

The trees that are left are most likely wildlife trees left as required by the Forest Practices Rules.

Oregon Forest Practices Rules require that landowners leave two standing live or dead trees per acre that are greater than 11 inches in diameter on all clearcut logging units that are 25 acres or larger. They also are required to leave two down logs per acre. Trees are sometimes left as single trees spread throughout a harvest unit, or they can be clumped in groups or along the edges of units to make logging and follow-up management easier, and to have leave trees that are less likely to blow down.

These standing leave trees provide structure in the new forest, which can help provide habitat for certain species of wildlife. The role of standing live and dead trees and down logs for wildlife habitat is discussed in an OFRI publication titled: "Wildlife in Managed Forests: Oregon Forests as Habitat." Copies of this publication can be ordered for free or downloaded at the OregonForests.org website: https://oregonforests.org/publication-library/wildlife-managed-forests-oregon-forests-habitat.

I hope this helps answer your question. Thanks for asking a forester.

Is logging allowed very close to a creek or river? Is the landowner required to get a permit?

Timber harvest on private timberland in Oregon is regulated by the Oregon Forest Practices Act & Rules. Landowners or their loggers are required to file a Notification of Operations at least 14 days prior to any timber harvest with the Oregon Department of Forestry. They are generally required to leave riparian management areas consisting of a live tree buffer along both sides of any streams that contain fish or have a registered domestic water source. The size of the buffers range from 50-100 feet on each side of the stream, depending on stream size.

If you have concerns about a specific piece of property, you should contact a Stewardship Forester with the Oregon Department of Forestry in the area where the land in question is located. The following link has can be used to access a list of all ODF offices and Stewardship Foresters: http://www.oregon.gov/odf/privateforests/pages/findforester.aspx .

Thanks for asking a forester

I heard that some of the logs cleared out in a forest aren't used for construction because they have defects, and people can request to get these logs dumped at their property to use in their fireplaces. Is this true?

Great question. I am sorry to say this is not true, as far as I know. These defective logs are known as culls. They are fairly low in value, but can still usually pay their way out of the woods, as pulp logs or energy logs.

Those that can't be harvested at a profit are left in the woods where they become habitat for several species of wildlife. In fact, the Oregon Forest Practices Act requires that two down logs and two standing live or dead trees be left for wildlife habitat.

Thanks for asking a forester.

Can you explain the rule of replantation after cutting down trees in Oregon?

Basically the law requires that whenever logging reduces the stocking of trees below a certain level, then planting must be done to bring the stocking back up to that level.

The stocking level varies by site quality, with lower numbers allowed on poorer sites and higher numbers required on better sites. On typical western Oregon sites, whenever the number of trees is reduced below 120 trees per acre, then seedlings must be planted. The total number of seedlings planted varies with the stocking of the residual stand. If a stand is clearcut, then at least 200 trees per acre must be planted by two years after logging and be free-to-grow at the end of six years after logging.

Most landowners plant 300-400 trees per acre depending on seedling size and site quality.

These reforestation rules, and all rules under the Oregon Forest Practices Act, are enforced by Stewardship Foresters with the Oregon Department of Forestry.

I hope this answers your question. Let me know if you need clarification. Thanks for asking a forester.

A logging company came in and clearcut a 25-acre parcel that borders our farm. It has not been replanted and is currently up for sale. I understand that they have 2 years to replant, but if a person were to buy that land

... and didn’t want it replanted, would that be legal? My brother was thinking of buying it and since it’s already cleared and not replanted, could he run cattle on it and not replant if he bought it?

A: You are correct in stating that replanting is required within 2 years of logging. If the land is sold between the harvest and the planting, the obligation to plant trees goes with the land. The new owner will be responsible to plant trees if the land is to be kept in designated forestland.

The landowner may apply to the county for a land use designation change from designated forestland to another class such as grazing. If the county approves the land use change, then the reforestation requirement is waived.

Your brother should check with the county to see how the land is designated. Many parcels of forest are zoned agriculture or rural residential, so a waiver to the tree planting may be easy to obtain. In some other situations, the property taxes were reduced because of the land being forested. In those cases, some back taxes may be owed in order to change land use.

I hope this helps. Thanks for asking a forester.

Why are some clearcuts on Highway 26 in Oregon, toward the beach, so far past the replant date?

Oregonians have a long history of treasuring and protecting our natural resources. The Oregon Forest Practices Act, which started in 1971, does have strict laws and guidelines related to clearcutting and reforestation for private and state forestlands.

Rules to Live By is a publication that provides highlights of the Forest Practices Act. You can find information on page 5 about reforestation and pages 8-9 about clearcutting rules.

It is a law for landowners to replant within two years of harvesting. Within six years of harvest, the young trees must be “free-to-grow.” That means they are vigorous and tall enough to out-compete grass and brush, and will grow into a new forest.

Often it is hard to see the newly planted seedlings, as they are small, and it may take several years for them to grow tall enough to be seen, especially if there’s a lot of underbrush.

Stewardship Foresters with the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) ensure private landowners are complying with the rules. You refer to clearcuts along Highway 26 toward the coast. I have attached a map that shows regions of Oregon and the current contacts for the ODF Stewardship Forester. If you believe there has been a violation of the Forest Practices Act, it should be reported to the ODF Stewardship Forester for that area.

An additional resource you may find beneficial is a website called Knowyourforest.org

This website has an Assistance Map with contact information for various counties in Oregon. You can find phone numbers and email addresses for the Stewardship Foresters and OSU Forestry and Natural Resources Extension Agents serving your area.

Highway 26 to the coast is most likely either in Washington or Clatsop counties:

http://knowyourforest.org/assistance-map/washington

http://knowyourforest.org/assistance-map/clatsop

We hope you continue exploring and recreating in Oregon forests. The future and long-term sustainability of our forests are important to us all.

Thanks for asking A forester.

I have a couple blue spruces i have been growing for a couple years. I wish to plant them on public lands because I live in an apartment. Where can I plant them in Oregon?

It is nice of you to want to donate your trees. However, since blue spruce is not native to Oregon, I don't think they will be allowed on public forestland in Oregon. Federal and state land managers are committed to supporting native ecosystems that contain only native species.

The best place for blue spruce is in a yard or a park. You might contact Portland Parks and Rec or Metro Open Space to see if they could identify a spot for you to plant them.

We want to harvest timber- but not by falling. I intend to cut deadfall from across the 88 acres, haul it out, limb it, and then sell it to a mill or find a portable mill if the wood is good enough to make economic sense ...

... My question is: do I have to submit the same notification paperwork to take deadfall from across the property? It seems to me to be routine fire/ladder fuel prevention, with potential profit. I am happy to pay taxes, but the paperwork requests a specific swath of land to be designated, and I intend to pull a little here, a little there of already down trees. I work for the Forest Service and understand the importance of bureaucracy, but here I am "stumped" Thank you for any insight! I imagine the deadfall is mainly pine and fir.

A: This is an interesting question.

My understanding is that a Notification of Operations needs to be filed with the Oregon Department of Forestry in all cases of commercial timber harvest and thinning, even if the trees are dead. In addition to notifying the Stewardship Forester about harvest, the notification also notifies the ODF fire people that you will be operating power machinery, and the Department of Revenue people that taxes may be due.

I believe that it is possible to complete the notification stating that the harvest will take place across the property.

You may want to check with an ODF Stewardship Forester for a more exact answer. If your parcel is west of I-5 in Lane County, contact the West Lane ODF office in Veneta at 541-935-2283.

How can I get a landowner to replant after harvesting timber? It's been over three years, since harvest and there has been no movement towards reforestation. I don't know what I can do, to hopefully get landowner to comply with Oregon law.

Planting after timber harvest is required by the Oregon Forest Practices Rules. Enforcement of the rules is the responsibility of the Oregon Department of Forestry and the foresters who do the enforcement are called Stewardship Foresters.

Your best bet to getting a landowner motivated for replanting is to contact your local Stewardship Forester. If you click on the following link, it takes you to the ODF Private Forest’s “Find a Forester” page:

https://www.oregon.gov/odf/Working/Pages/FindAForester.aspx

When you click on the area in question, usually a county of part of a county, a pop-up box will give you the name and contact info for the Stewardship Forester in that area.

When you contact the Stewardship Forester with the address or legal description of the property in question, they will pay a visit and take enforcement action. They generally try for voluntary compliance first, but can follow up with fines and can even take over the planting of trees and send the landowner a bill. In a worse case scenario, a landowner could have a lien placed on the property and possibly lose the property. This rarely happens, but the fact that it could is a great motivator.

I hope this answer helps. Successful reforestation after timber harvest is essential in making forest management sustainable.

Thanks for Asking a Forester.

Is there anything in Oregon Forestry law that designates the hours in the day that companies may or may not be harvesting trees?

Thanks for your question. I know that chainsaws, log trucks and other equipment can be very loud in the early morning when you are trying to sleep. I am sorry that they are disturbing your neighborhood. I live in farm country near some vineyards and when the grapes start to ripen, the farmers shoot off propane cannons to keep the birds from eating their grapes in the early morning hours. We also have been hearing crop dusters over the hazel orchards at about 5 a.m. lately. I think of it as part of the joy of rural life. Ear plugs can also help block the noise.

As far as I know, there is nothing in Oregon forestry law that limits how early operations can begin in the day, as long as they can be conducted safely. However, now that it is Fire Season, there will soon be limits as to how late the loggers can run chainsaws and other motorized equipment in the woods. When we go to Industrial Fire Precaution Level II, chainsaws and other motorized equipment generally need to stop running at 1 p.m. and can't start up until after 8 p.m. During fire season the loggers try to start work as soon as it is light enough to work safely. If the loggers don't start early, they don't get a full day's work in, before the 1p.m. shutdown. When fire danger gets to IFPL III, chainsaws and motorized equipment are not allowed off the roads. At IFPL IV, the woods are closed. The woods are eerily quiet then.

The good news is that every day this time of year, the sun comes up a few minutes later. We are blessed in Oregon to have thriving forest products and agriculture industries. I think that a little noise for a short while is worth having the jobs, taxes and products that are generated by these industries. Thank you for being understanding.

I hope this answers helps you and your HOA. Feel free to share this reply with your members.

I've been reading about climate change and it's frightening. I read that trees are absorbing the C02 but they are being cut down faster than we can replace them and we have less than ten years to stop the warming. Any trees we plant now certainly can't

Thank you for your inquiry to the Oregon Forest Resources Institute (OFRI) regarding trees and carbon.

We agree that climate change is a very real worry and that our forests and how we manage them are part of the solution. I also agree that planting trees is a good thing to do to fight climate change, but it is way too slow in acting to be our only response.

Here are two OFRI resources that may be of some interest to you:

1. OFRI Carbon and Forestry Fact Sheet &

2. OFRI 2019-20 Oregon Forest Facts

These resources make a few important points on the subject:

1. Growing Trees Accumulate Carbon – on page 5 of the Oregon Forest Facts is a graph that shows Oregon is growing much more wood than we are harvesting or losing to mortality – This means we store more carbon in our forest every year.

2. There is considerable mortality (25% on average) in our forests through fire, diseases and insects. This eventually converts stored carbon in our forests back to atmospheric CO2 by burning or decaying wood. This is mostly because of the high mortality (36%) on federal forests.

3. Oregon has done a great job of protecting our forest land from conversion to other land uses. We have over 94% of forest cover we had in 1907 and as the graph on page 3 of OFF 2019-20 shows, we have held our forest land base nearly steady at about 30 million acres since 1953.

4. Wood products store carbon for the long-term and as shown on pages 8-10 of OFF 2019-20, Oregon produces more wood products than any other state.

One of the points made by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is that actively managing forests for wood production is one of the best things we can do to promote forest landownership and thus carbon sequestration.

Thanks for caring about Oregon's forests and climate.

We piled split wood next to our fence. On the other side of the fence, our neighbors have a privacy row of Douglas-fir trees. (I think they are Douglas-fir.) I do not know for sure what kind of wood I stacked, since it was free on the side of the road ..

... My question is: Will wood that is drying out kill the fir trees? Three of the fir trees are drying up and dying. The rest of the row of firs is perfectly fine. The entire row of stacked wood is not the same, as far as I know. It could be the same kind of wood, but definitely came from different areas. None came from out of state; it all came from different areas of my city. As far as I know none of the wood is pine, as we know pine isn't a best choice for the chimney.

A: Some dead wood can contain bark beetles and wood borers, so there is a possibility that insects emerging from the firewood could attack Douglas-fir near where it is stacked. However, I doubt that the death of the trees in your neighbor's privacy row can be attributed to your firewood.

As documented in the blog linked here, there is a lot of Douglas-fir death showing up recently:

http://oregonforests.org/blog/many-douglas-fir-dead-tops-and-branches-willamette-valley-year

Trees in privacy rows are especially susceptible to this problem, because they are planted close together. The big problem is a few years of drought. Douglas-fir that are healthy are fairly resistant to bark beetles and wood borers. These insects are all around us nearly all the time, and can fly for miles to find a weak tree to attack. Studies have shown that stressed trees give off pheromone-like substances that attract bark beetles and wood borers.

You might share the blog with you neighbor. The dying trees are likely goners, but thinning remaining trees to give them more space and giving them a good deep drink of water could help the survivors to keep going.

I hope this answer helps. Thanks for asking a forester.